Ankita is committed to building a future where all children and families thrive and flourish. She has over ten years of global experience working on her mission through partnerships with city agencies and the private, non-profit, and philanthropic sectors. She is the Director of Climate Program at Capita, an independent, nonpartisan think tank with a global focus. Previously, Ankita served as the Knowledge for Policy Director at Bernard Van Leer Foundation. She led a multi-functional team responsible for sharing tools, knowledge, and resources for advancing early childhood policy that supports the well-being of children and caregivers in cities.

Michal Matlon: You work on creating cities that are good for children. What does that mean?

Ankita Chachra: Nurturing environments and loving and attentive caregivers are the cornerstones of a healthy, happy, and thriving childhood. Babies need food, sleep, and security, and much of that depends on the caregiver, given their limited mobility in the early years.

Going even further, there are studies that point out how a woman’s mental health during pregnancy and her chronic stress have a direct impact on the outcomes for the child and their development.

This aspect of psychology fascinates me because how well we can take care of children inherently depends on how well we can care for adult caregivers and their mental health.

How do we create a low-stress environment so we can not only support but enhance caring for a child? If the built environment doesn’t support caregivers and needs of children, care-giving itself becomes a challenge.

Imagine you’re standing on the street with a one-and-a-half-year-old child who’s just starting to walk, and you’re trying to drop her off at a friend’s house and then go to the store. You only have three hours before you have to come back.

The street has no shade. It’s a hot summer day; you can hear cars honking and smell the pollution. You must cross a wide street to catch the bus, which only comes every twenty minutes. So, in the stress of trying to cross the street and make it all work, how much attention do you give to the child? Where is the time for responsive care and connection?

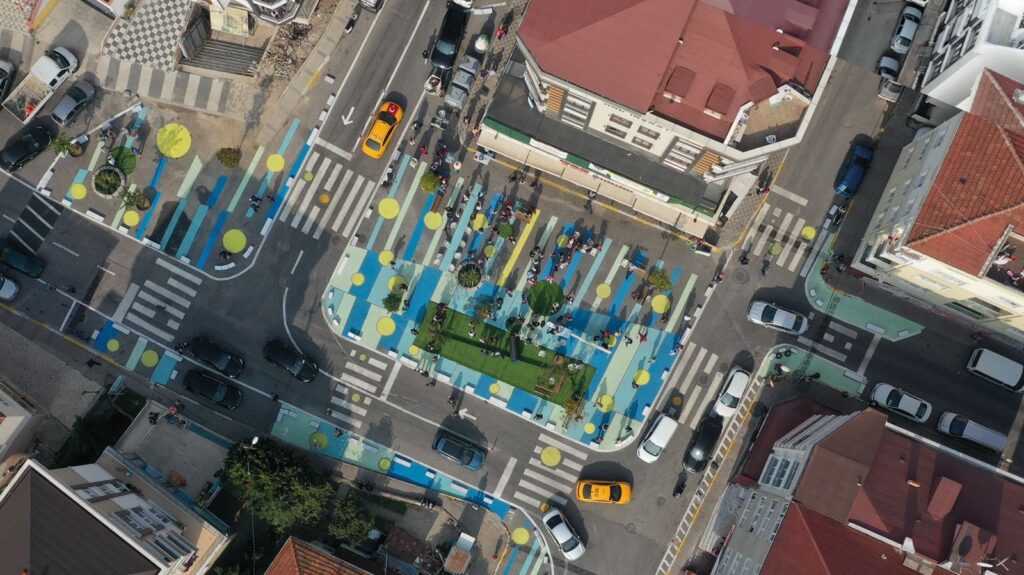

Now imagine a different scenario where there’s shade and you can cross the street comfortably without worrying about missing the bus that comes every five minutes. So, if you miss one, no big deal.

The structure where you’ll be waiting is shaded. There’s a play area for kids to keep them occupied for the five minutes, or you can converse with them. It’s a comfortable environment. You don’t hear horns every minute.

It’s a very different environment. You have time to turn to your child and say, “Oh, see that bird over there? What color is that bird? See that fruit over there? What color is the fruit?” That’s where you start to see that the built environment has such a big impact, especially when talking about caregivers and children.

And this is something psychology talks about – stimulation, how interesting or boring a place is, how chaotic or calm it is, and how much it can overwhelm your brain. It’s also about the conversations you can have with kids at that point.

For me, it’s enjoyable when I take my son for a walk in the park, and I point out a flower and ask him what color it is or let him interact with the sand or the water. However, if I’m just walking down a loud and car-centric street and I’m worried about the noise, safety and speeding cars, I’m not able to engage as much.

Designing Spaces for Children Is Not Just About Playgrounds

Michal: People often think of places for children as something separate from the street. But you mentioned that you still interact with that environment, even when walking somewhere or waiting. Even the ordinary everyday street should provide enough interesting stimuli or opportunities for learning or interaction for children.

Ankita: Yes, Tim Gill in his book “The Urban Playground” and Professor Peter Norton in his book Fighting Traffic: The Dawn of the Motor Age in the American City both talk a lot about the history and development of our cities.

Tim Gill points out that playgrounds were designed to give children a safe place to go because the streets became unsafe as cars took over. Streets used to be where life happened – retail, children playing, socializing. The whole idea of cities and children has been reduced to playgrounds.

Of course, playgrounds are important, and we need to invest in them. Still, it’s also about how children get from their homes to playgrounds, what kind of homes they live in, whether spaces they spend time in have natural light, the schools and food they have access to, and whether they are comfortable and inspiring places for exploration and learning in nature or just asphalt schoolyards.

I often notice a lack of greenery in schoolyards and playgrounds in my neighborhood, with an unfortunate abundance of asphalt and concrete surfaces.

Michal: I’ve heard of New York’s daycare centers in basements and some without windows.

Ankita: New York, like many other cities, requires urgent climate adaptation for its child and family programs and infrastructure. A report by the Low Income Investment Fund highlights that 38% of childcare providers in New York City operate from homes with directly accessible basement space and about 80% of these face significant risks due to increasing sea levels and intense flooding and rainfall.

That’s a significant vulnerability, given the frequency of flooding due to climate change. And this is key infrastructure for children and families that are vulnerable and at risk.

About eighty-five percent of the brain develops from birth to age five. Every experience and interaction during this time shapes our foundation.

When we were looking for child care for my son and as I was mapping schools in our neighborhood, I noticed that most schools are next to major highways, which further raises concerns about air quality and children’s respiratory health. This reflects a lack of value placed on childhood and early development, which is fundamental to our lives.

The early years are a big window of opportunity. Every positive experience and interaction during this time shapes our foundation for healthy and resilient adulthood. About eighty-five percent of the brain develops from birth to age five.

We need to value the early years of development more and recognize the effort parents put into raising their children. It’s not just about playgrounds; the entire city must serve its residents, including children, parents, and grandparents, who often care for children while parents work.

Children Help Us Become More Sensitive to Our Environment

Michal: It seems to me that just as an environment that is good for adults benefits children, the reverse is also true: an environment that is good for children benefits adults. Children are more sensitive to their surroundings.

Ankita: Increasing environmental sensitivity benefits everyone by raising the bar for design. For example, designing sidewalks with ramps benefits not only children and strollers but also people with mobility challenges. Or maybe you’ve got a heavy suitcase that you roll down the sidewalk.

This approach benefits everyone in the community and promotes inclusivity. Investing in the early years has multiple societal benefits, from reducing crime to improving mental health outcomes.

Learning about this was an eye-opener for me. As a woman of color, I’ve always wanted to work on equitable cities. And the child lens fits well with the gender lens, especially since women are still often the primary caregivers. Creating safer spaces for children also creates safer spaces for women. We must design environments that allow children to be outside to access nature, not just sit at home.

The Streets for Children team in Bratislava did a study similar to Tim Gill’s that showed that children today have limited mobility compared to previous generations. This shows that we need to build cities where children can freely explore and play.

Children’s Freedom to Roam in Cities

Michal: I find the topic of children’s autonomy quite interesting. There’s a Japanese show called Old Enough! that sends kids between the ages of three and six out on various errands.

Ankita: I lived in the Netherlands. Every year, there’s a study about where children are the happiest, and the Netherlands often comes out on top. A big part of that is children’s autonomy, especially with safe infrastructure for biking from a young age. It saves parents time and allows children to do more on their own.

But I’ve also been thinking about the impact of culture. Growing up in India, children were out and about in public spaces at all hours, interacting with others.

In many Western societies, there’s an emphasis on parents doing everything themselves, which leads to strict bedtimes and children being less visible in public spaces after certain hours. I think visibility plays a role in recognizing and meeting children’s needs.

Including children in public spaces leads to better-designed spaces. For example, every café and space I visited in Dubai had a space for children, integrating them into every aspect of society. Other cities, like Addis Ababa, are investing in the early years to tackle big challenges of poverty.

Bogota has been leading the way for not only creating safe and healthy spaces for children but also now investing in care blocks that provide care for the caregivers.

And the initiatives in Tirana that have prioritized the needs of children as a way to build a city of the future. Milan’s school street and plaza programs prioritize mobility, even providing bike seats in bike-share for children.

And here, in Bratislava, mayor Vallo’’s vision and the Start with Children initiative are exciting and inspiring! The mayor doesn’t just talk about creating more playgrounds; he envisions a city that serves everyone, starting rightly so, with children and caregivers.

Because it’s all interconnected, from streets to public spaces to schools to housing. Cities recognize children and parents as key stakeholders essential to a vibrant, welcoming, comfortable urban environment.

Michal: It seems to align with the movement to make cities softer, right?

Ankita: Designing cities for care and caregiving is critical. Caregivers move around the city in different ways. For example, as a caregiver especially for a baby or a toddler, my routine revolved around my son’s nap and meal times. I was “trip chaining,” going from one place to another, which required well-connected transportation systems.

Designing cities from a caregiver’s perspective means thinking about connected neighborhoods and the time between activities, like meals and naps, critical to children’s well-being.

It’s just part of being human. Children listen to their bodies, as adults should, but it’s interesting because adults can ignore those needs. Children can teach us much about what we need to learn about ourselves as adults.

Children can teach us much about what we need to learn about ourselves as adults.

So if you think from a caregiver’s perspective about how they travel, the services they need, and the distance they travel, especially in terms of food, naps, and diaper changes, you can only go so far, like the concept of 15-minute cities that’s becoming more popular.

That’s the distance you’re willing to go, like walking to a park within 15 minutes. Anything beyond that becomes less accessible in the early years of life. Of course, as they get older, you can change those patterns.

Bogota’s care blocks are a wonderful concept. They provide care not only for children but also for other family members who contribute to caregiving. Caregivers can enroll in classes or courses while children are engaged in activities, fostering social connections among caregivers.

I am also reminded of Lima, which launched an interesting program during COVID lockdowns called “Lima Tu Cuida or Lima Cares” that focused on children and caregivers.

Building Community Around the Kids

Michal: There’s also an interesting observation that we have this strict separation of children’s activities and adult activities. When children go to the playground, parents have to watch and supervise them. But in smaller communities or villages, there’s more of a community care dynamic, where everyone watches the children as they roam around.

Ankita: Absolutely! It’s also about the eyes on the street. We’ve segregated playgrounds into special areas, but in the past, and in some parts of the world, playgrounds were surrounded by houses.

Parents could look down from balconies or watch their children while they cooked. Neighborhoods have the potential to create thriving lives. This shift from community design to segregation has led to many of our current problems.

Michal: I feel like it really works, and people are inspired by it. My friends live in this old city block with buildings around it and a little park with a playground in the middle. People feel a sense of community there. They know their neighbors who take their kids there, and things happen organically. Parents start talking, kids play, and they help each other.

Ankita: Parents understand each other’s challenges and support each other. Playgrounds become places where families connect, and you see the same people in the neighborhood. It’s about creating solidarity and reducing loneliness through community connections, which is critical to our well-being.

At Capita, in our mission to build a future in which all children flourish, we focus on two key areas, one, addressing the impacts of the childing climate on young children and two, building a culture of solidarity and care.

This is particularly relevant now that the majority of parents are from Generation Z, and they’re struggling with loneliness, anxiety and other challenges. We want to foster connections and create support networks for families.

How Sustainability and Children Go Together in Cities

Michal: You’re also working on sustainability and climate change at Capita. How does this relate to making cities suitable for children?

Ankita: With climate, there’s a significant health component to consider. Healthy, resilient children are the foundation of healthy societies. Children are the least responsible for climate change but will bear the brunt of its effects.

Nearly ninety percent of the global burden of disease caused by climate change will be borne by children under the age of five. This is a global health crisis that we must urgently address. Climate change directly affects the health and well-being of children, and we must act now to protect their future.

Children are the least responsible for climate change but will bear the brunt of its effects.

Adaptation is also urgent. In June 2023, New York City’s air quality changed dramatically because of forest fires in Canada. Suddenly, we were all trying to figure out how to navigate the time children spend outdoors, from getting to and from daycare to getting time outside to play in this poor air quality.

Children are also more susceptible to asthma because their lungs are still developing, and they breathe 4 times faster than adults. They take in more air for their body weight, which means bad air affects them more than adults. Poor air quality is extremely harmful to children.

You can’t put a mask on a one-year-old and take him to daycare. At that moment, I thought all these efforts to reduce carbon emissions, create more bike lanes, or switch to greener energy sources were important, but so is the urgent need to adapt our environments now

Similarly, when we think of increasing heat waves, they pose a significant risk to children’s health. Buildings and public infrastructure in many cities were never designed to withstand these temperatures.

Cities have the potential to make significant changes, from the design of housing systems through retrofitting them for passive cooling and heating to integrating greener energy sources.

Shade is vital in the summer, especially in areas that have been historically neglected due to practices such as redlining (withdrawing financing from minority neighborhoods).

Neighborhoods that lack trees and shade have significantly higher ambient temperatures compared to areas with more green and tree cover. That’s why this is a critical issue that we need to address from an adaptation and health perspective.

By starting with children and meeting their needs, we can create neighborhoods that incorporate shade into street design, use natural materials that absorb water, and create safer, cooler environments. These practical design considerations can address climate and solidarity, fostering thriving communities.

Rebuilding Children’s Connection With Nature

Michal: It’s quite interesting how the vision of a good city changes over time. Ten or fifteen years ago, there were visions of cities that separated people from nature, living in massive towers and leaving nature untouched. But now the focus is on building cities fully integrated with nature that benefit people both physically and mentally.

We’re realizing the power of nature, especially when it comes to adapting to the effects of climate change, such as heat waves, floods, or heavy rains. Nature offers solutions that we should harness for sustainable urban development.

Ankita: Exactly. The benefits of nature extend beyond physical health to mental health and cognition, benefiting both children and adults. But our past neglect of working with and in harmony with nature has only exacerbated challenges like flooding and extreme heat.

We realize how much children slow us down. And it allows us to think about our world differently.

We need to act now and prioritize climate adaptation in every decision we make for our cities. Children are not only our future. They are our present, and we need to recognize that our decisions on climate adaptation and resilience impact their future and present.

Michal: Another aspect of sustainability is raising a generation with a new attitude toward nature, protecting it, spending time in it, and making sustainable choices. There was an inspiring project in Utrecht where they turned a highway through the city back into a water canal. Now, people can use it for recreation and transportation in a more sustainable way.

Ankita: This reminds me of Cheonggyecheon in Seoul. They removed a multi-lane highway to restore the river that used to flow there. These examples show how cities are reintegrating nature into urban life.

I have an anecdotal story. I grew up in India, and in Delhi, access to nature was limited, mostly to driving to the mountains or going to a park. On the other hand, my partner grew up with daily access to nature. He lived near a forest reserve, and his grandparents often took him on nature walks.

As an adult, I can see the stark difference in our comfort level with nature. His upbringing instilled in him a deep appreciation and stewardship of nature. This contrast made me think about how we teach children the value of nature.

Nature is seen as a third parent in some Latin American and indigenous communities. Children are taught to care for nature as it cares for them. This relationship-centered approach to environmental education is fascinating. It emphasizes reciprocity and stewardship and highlights the interconnectedness of humans and nature.

So I’m thinking, how do I expose my children to nature and cultivate their relationship with nature so that they understand their responsibility to care for it when they grow up?

There was a study where they gave children natural materials like flowers, leaves, and rocks, and then they gave them plastic objects. The researchers examined the number of words used, the feelings described, and the conversations started.

They rated the quality of the children’s play and conversation. There was a big difference in the number of words used and the richness of imagination when they used natural materials compared to plastic.

We talk a lot about early childhood brain development and how different experiences influence it. Nature provides all the things that toys try to mimic. From a sensory experience, if you take a child to the beach, the sand, the water, the sound, the ability to run barefoot, the ability to pick up and throw pebbles, it’s right there.

From a sensory experience, if you take a child to the beach, the sand, the water, the sound, the ability to run barefoot, the ability to pick up and throw pebbles, it’s right there.

From a learning and educational perspective, all these tools that we’ve developed in our lives, if you go back to nature, you can do all that there. You can learn about physics, you can learn about biology, and how nature works. That’s why cities need more nature-based spaces or even animal interactions to show that we are part of the same ecosystem.

When I moved to the Netherlands, it was the first time I thought, “Oh my God, I’m actually looking at ducks in a public space.” Even as an adult, I was so excited because I wasn’t used to seeing them in New York or Delhi, where I grew up. You had to go to a special place to see them.

Michal: So a space that is good for animals is also good for children.

Ankita: Caring for our children and caring for our planet is inextricably linked. We just look at life differently. We realize how much children slow us down. And it allows us to think about our world differently.

It inspires us to move away from practices that are not healthy for adults to slow down and enjoy and run free like a child, to be in awe of a butterfly or a flower. We don’t often do that as adults.

Enjoyed this article?

Support our mission with just €1! Your donation keeps our website running and supports the spread of knowledge about creating places that are good for people.